Do you know the essential parts of a story — or why they’re essential?

Think back to the last story you read (or listened to) that captured your imagination and held onto it to the end.

Chances are the story elements described in this were responsible for that.

And you can probably point to at least one of them and remember how that element in the story took hold of you.

Consider the questions a journalist would ask when writing a story:

- “Who?” = characters, point of view (POV)

- “What?” = plot, theme, symbolism, conflict

- “When?” = setting

- “Where?” = setting

- “Why?” = plot, theme, conflict, morals/messages, perspective

- “How?” = plot, theme/s, resolution

Once you understand the elements and why every story needs them, you’ll be able to read any short story or novel, identify its parts, and understand why its treatment of those parts has left you with the impression you have.

And if the story is a dud, you’ll also likely think of ways to make it better.

5 Parts of a Story that are Foundational

1. Plot of the Story

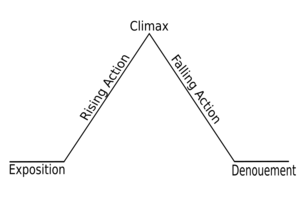

In 1863, German playwright and novelist Gustave Freytag wrote Die Technik des Dramas in defense of the 5-act dramatic structure.

His study gave us what we call Freytag’s Pyramid, which breaks down the plot into five key elements:

- Exposition (or introduction)

- Rising action (rise)

- Climax

- Falling action (fall or return)

- Catastrophe, denouement, resolution, or revelation (finale)

The diagram shown above puts the climax at the top and in the middle of it all, which doesn’t necessarily mean it happens in the middle of the story.

The exposition is basically the story’s introduction, where we meet the main character, get a feel for the setting and other essential details, and learn what’s at stake.

Then plenty more happens during the rising action that leads the reader to that moment of truth — or “the point of no return” or whatever pithy phrase comes to mind when someone asks you, “What is the climax?”

It’s the thing we hope our readers recognize. No one wants to hear, “Are we there yet?” when what was supposed to be the climax has already happened.

And on the downturn, during the falling action, we want to see loose threads gathered and neatly tied up. We want to see the consequences of whatever happened at the climax.

We also want to see story plots with a satisfying resolution. And when that resolution comes at the end of the story, it could be a catastrophe. Or it could be what the reader hoped would happen.

Or it could be neither.

To learn more on writing a plot, click here.

2. Characters of the Story

Your characters are the people who make the story happen — or to whom the story happens.

It’s important to note, too, that none of the characters have to be human (or even human-shaped). Your favorite character might be a dog, a centaur, a sentient tree, or something completely different.

The main thing you want your main character to have is a clear goal. Your most important characters should want something. And something or someone should stand in the way.

3. Setting

The setting of a story deals with the where and when — the places your characters go, the era in which the story happens, the time of the year, the times of a day, and so on.

It also includes details like the weather, the language is spoken, cultural norms, the political climate, and other things that can influence your other story elements.

Setting can change from scene to scene, and the setting itself can even serve as a character. It can also provide symbolism and hint at the story’s overall message.

How the narrator describes the setting can also offer clues about the perspectives involved.

An effective setting is neither more nor less than everything your story needs it to be.

4. Resolution

Story plots with a weak resolution or those that leave the reader hanging deserve the contempt heaped upon them.

The resolution answers the questions lingering in the reader’s mind:

- Did the main character get what they want?

- What has the antagonist achieved?

- What will be the outcome for all the characters who matter to me?

Some endings leave a thread or two unresolved or open to the reader’s interpretation. This can work as long as the resolution answers the reader’s most pressing questions in a satisfying way.

5. Themes

The theme of a story tells you something about why it was told and how the story relates to the bigger picture of existence. It explores questions and ideas that have been with us for millennia, if not from the beginning.

The theme provides a framework for the story and ties it to universal human experience, making it more relatable and memorable.

Did you get value from this?

If you’ve liked this post and found it useful, please just take a moment to share it on your social media platforms to help and encourage authors.

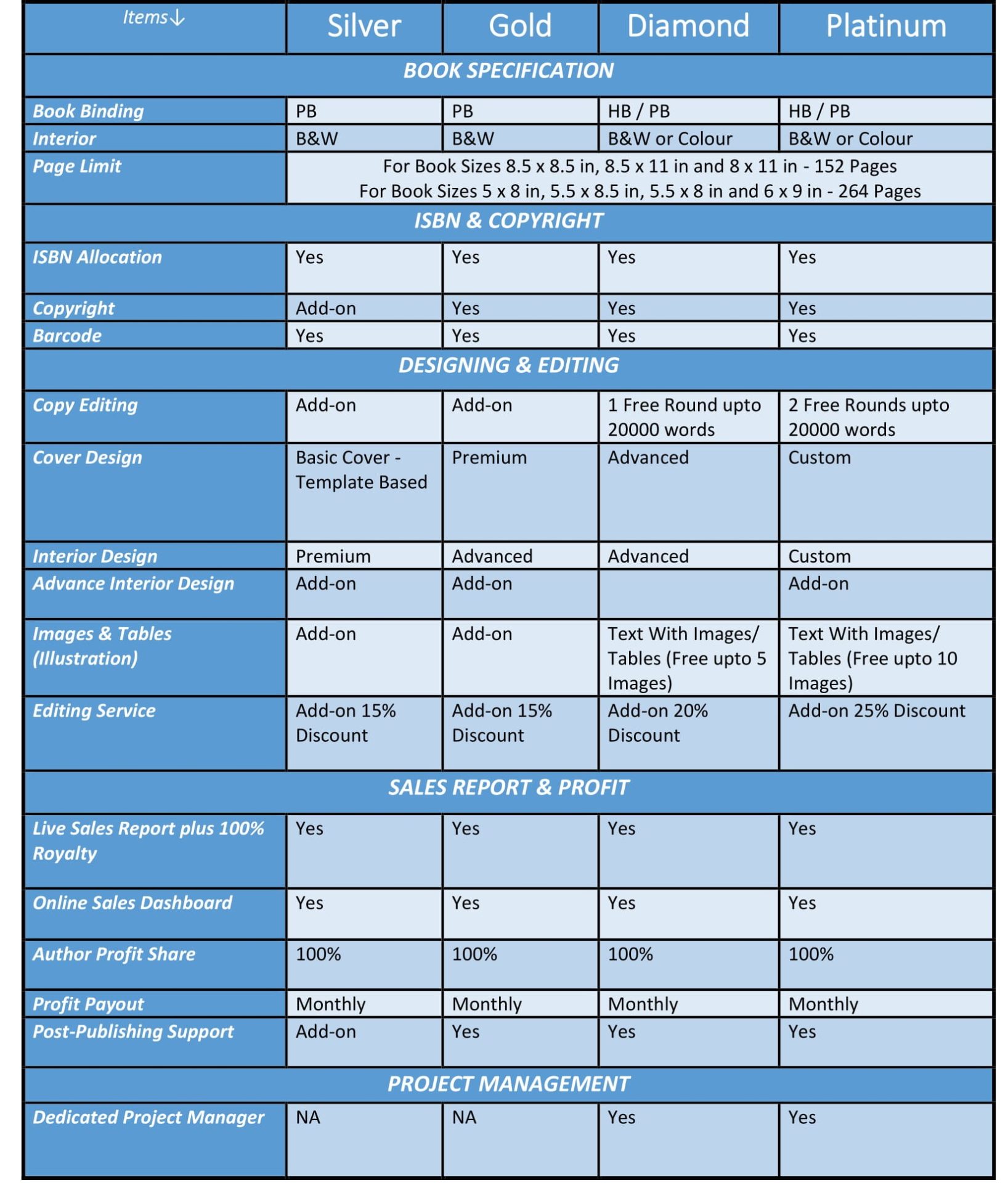

Contact Ink Your Thought For self-Publishing details, plans, and to know more about children and education books kindly visit Sheth Books.

Also for more details on self-publishing visit Authority Pub

Follow us on: